“Please speak of how you view the possibility of attachment to non attachment,” I ask the dharma teacher.

I am at Kopan Monastery to heal my body and mind from resonating at the frequency of the fatal diseases I might have contracted from the dog bite, and to recover from setbacks encountered on the home front. On a three-day water fast, I travel the darkened tunnels of a healing crisis with fever and fitfulness and I find the comforting containment of 700 monks and nuns chanting and performing pooja to be instrumental in my wellness.

I notice, as I ask the question, my hand running fingers through the thin blonde hair I have always equated with femininity as I admire the teacher’s beautifully smooth-shaven crown. I am drawn to life in a nunnery and commit to shave my head on my arrival in India … yet I also know how fickle I can be. Life as a renunciate mocks me as I consider relinquishing the bower bird aspects of my identity … the beautiful shiny objects I have around me, even on my travels.

I sit each morning as an observer, an outsider looking in on the monks as they arrive dressed in robes that simultaneously shed their identity and give them one. They prostrate and take their seats. They are vessels, showing up in service to the prayers; chanting for others what others can’t do for themselves.

I sit and contemplate on no more than what I witness. The pooja, the music, the clapping away of evil spirits. When a British Colonel arrived in Lhasa after gunning down thousands of Tibetans, he is said to have felt great pride in the Tibetans clapping for him on his arrival, mistakingly believing their attempts to dispel evil as their celebrating his prowess.

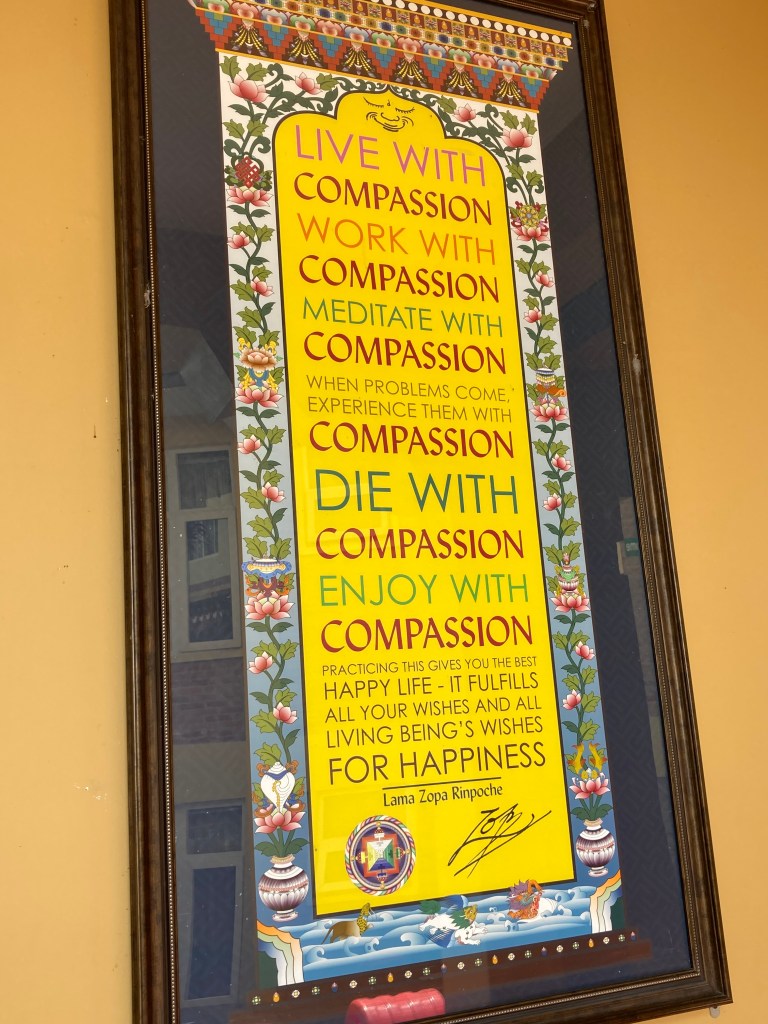

The opposite of doing is not apathy; it’s allowing … a yielding rather than a seeking. Meditation is an action. It is a deliberate and intentional allowing of all that is, in order to practice not attaching to any of it through the sense organs. Gathering to wash the plates and utensils from food preparations, the chatting and community is as profoundly important as the nourishment from the simple food. Quality of life is expressed through moving hands that find their intelligence in ordinary tasks. Is this what malas could be used for? I wonder.

As the fever passes, I feel both relief and disappointment. Relief that I may have healed myself from potential suffering. Disappointment that I may have saved myself from dying. If you know me, you will understand that this is not in fact a depressed dig in the darkness, but a lightening of something quite liberating. Regardless, a little more context may be required for those who don’t know the true meaning of the word GuRu and may be more attached to just the one syllable without considering its counterpart.

I have never felt fully committed to this incarnation. Call it trauma, abuse, nervous system dysregulation … no matter … contemplating death these past days, I recognise that I am more attached to death than I am to life. So the tears I shed are related to feeling that dying from a dog bite in a country that honours death as much as it honours life would be a better fate than ultimately taking that long walk into the ocean when I am done with this so-called me I am becoming less and less identified with as I travel to integrate the past five decades of my fabrication.

There is a middle ground always: not attached to either life or death but fully committed to and incarnated in both. Like a suspension bridge that must be fully rooted in both banks. Straddling. Clinging to neither … and also to both.

My writing habits have gone into holes and tunnels and transcended the notion of linear time. There are gaps … chasms. And, as with my meditation practice, I have to keep coming back to the cushion to start again.

I am in India now at Deer Park Institute in Himachal Pradesh. So much life has happened between my time here in February, and this time now. I have written less than I aspired to, traveled and explored way more than I imagined, connected, studied, expanded (and also contracted), integrated and shed so much of who I believed myself to be. To honour this new version of myself that can’t recognise myself in the mirror anymore, I travel to McLeodGanj, two hours each way by cab, to a hairdresser I met in February. My instruction to Mukti back then was still my usual, “Just the ends off please; I’m trying to grow it”. This time I am not bold enough for the full head shave—yet—but I flick through Pinterest to show him some images that match this new Penelope V11.9 and tell him to work his magic. I close my eyes and breathe.

This is the only death I need right now.

Monsoon season is a flushing of all the rubbish; a cleansing of the earth and a transition into autumn. India has six seasons instead of four … six opportunities to adapt or die.